Investors should worry if their funds have 5% or more in cash, say experts.

Market commentators discuss the uses of cash within a fund and whether a manager can ever hold too much.

- Patrick Sanders

- 5 min reading time

Source: Trustnet

Investors should seriously question if a fund they own has more than 5% in cash, according to asset allocators.

For Jason Hollands, managing director at BestInvest, 5% exposure to cash for extended periods is a “cause for concern” partially because in most funds, it would “easily be a top 10 position”.

At this allocation, ‘cash drag’ becomes a much more serious issue for investors, he explained.

Cash drag refers to the fact that cash has low to even negative real returns because inflation can often be higher than the yield on offer. This means that over time, the value of cash within a portfolio gets eroded and other assets need to outperform to compensate.

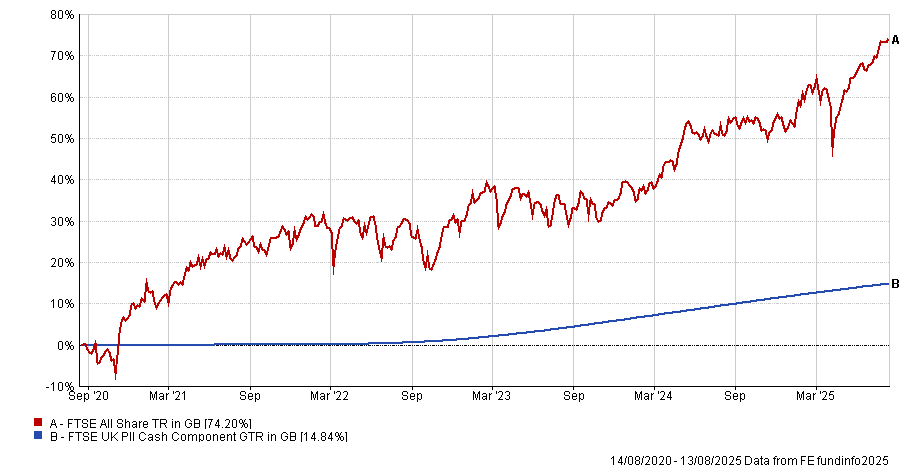

As a result, persistently high cash positions will often lag the performance of other assets during rising markets, Hollands added. This is demonstrated by the chart below, which shows that cash (measured through the FTSE UK PII Cash component) has lagged the UK stock market by more than 50 percentage points over five years.

Performance of indices over the past 5yrs

Source: FE Analytics.

Hollands continued that a 5% or higher cash allocation can also be concerning because fund buyers are still paying managers a fee, but managers are not fully investing it.

“As an investor, I’ll take my own view as to whether I want to be in the market or cash, so I expect my money to be fully invested,” Hollands concluded.

Andy O’Shea, investment director and head of fund solutions at Pharon Independent Financial Advisors, agreed that above 5% in cash for a persistent period would be when he “starts to raise questions with the manager”.

Certainly, he noted that this could be down to simply a matter of timing, such as when the fact sheet was produced or due to a surge in inflows, which meant the fund had yet to deploy its new cash balance.

However, he added that it could be the sign of a “lack of conviction”. This is particularly the case when managers have chosen to build up a defensive cash position as a temporary measure but have waited too long to get back into the market, turning this short-term cash allocation into a long-term drag on returns.

Paul Green, portfolio manager of the multi-manager range at Columbia Threadneedle, added: “It is important to ensure the manager is not backed into a corner on cash balances – waiting for a market crash that does not happen can be a hard psychological position to move away from.”

Liquidity and cash

However, while all three experts said there could be concerns with high cash balances in portfolios, they agreed that there are times when it is needed.

One example is when open-ended funds use it to fund redemptions, either because the portfolio is suffering outflows or because it invests in a less liquid asset class that requires having cash on hand just in case.

Hollands noted: “With money coming in and out of open-ended funds daily, having an element of liquidity to meet both redemptions or as a reflection of new money landing in the fund before being deployed in stocks is just a fact of life.”

A cash buffer means that if investors choose to pull out of an open-ended fund, managers do not have to be forced sellers of assets, which can have a significant negative impact on performance.

As a result, Hollands would also be nervous if a fund focused on less liquid assets, such as smaller companies, had a low allocation to cash, “as it could prove problematic in the event of a large redemption request”.

Columbia Threadneedle’s Green agreed that when a fund is facing persistently high outflows, a “higher cash balance than normal” can be crucial to ensure the fund is not forced to sell further assets.

Cash for caution

The other reason funds may use is cash is to get out of markets that appear expensive. O’Shea noted that “building up a war chest” could be appealing when managers believe markets have “got ahead of themselves”.

A temporarily high cash allocation can help shelter investors from the worst of a sell-off when markets are euphoric, allowing managers to redeploy capital when things calm down. This is part of the reason O’Shea raised the cash allocation in his model portfolio service to a recent high earlier this year.

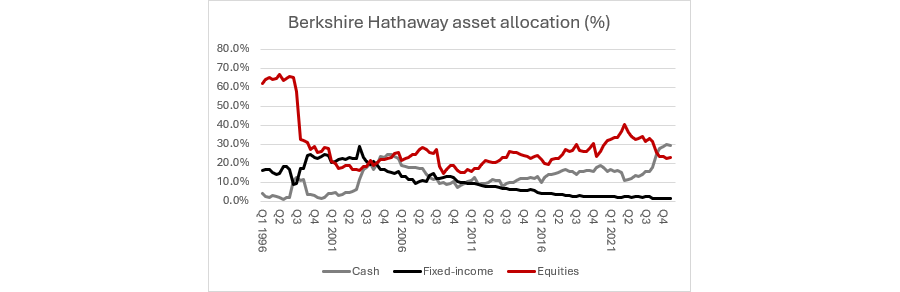

Russ Mould, investment director at AJ Bell, pointed to Berkshire Hathaway as a key example of using cash tactically. At various points in its history, it had cash stakes of well above 5%, as demonstrated by the chart below.

Source: AJ Bell. Berkshire Hathaway accounts. Investments only.

Despite asset allocators' reservations about a cash allocation this high, Mould noted that this approach has broadly paid off. “There have been periods in the past when Berkshire has lagged the S&P 500 only for its patient approach to accrue reward and generate huge outperformance over time.”.

For example, he pointed to the late 1990’s where instead of getting swept up in the scramble to buy tech, Berkshire Hathaway remained patient, “evading the slam that came in 2000-2003”.